Bear body maintenance techniques: Asian black bear nutritional strategies as seen from changes in fat accumulation over the course of a year

Bear body maintenance techniques

- Nutritional strategies of Asian black bears as seen from changes in fat accumulation over the course of a year -

An international joint research team led by Seigo Sawada, Director of the Shimane Center for Mountainous Areas, Professor Shinsuke Koike of the Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology Graduate School of Institute of Agriculture Division of Environment Conservation, Sam Steyaert Associate Professor of the Nord University of Norway (concurrent Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology Graduate School Institute of Global Innovation Research Associate Professor), and Kahoko Tochigi, Research Fellow at the National Institute for Environmental Studies, We analyzed the relationship between seasonal variations in fat accumulation and fat content in several locations of Asian black bears (hereinafter referred to as "bears") living in Shimane Prefecture and the masting of hard mast (so-called acorns), which are the main food in autumn. The results revealed that bear fat accumulation fluctuates seasonally, peaking in autumn and then decreasing not only during hibernation but also from spring to summer. It was also found that bears use subcutaneous fat first among fats, followed by visceral fat and bone marrow fat as an energy source. In addition, it became clear that in years when acorns do not have a good masting, not only do they not accumulate enough fat in the fall, but the effects will reverberate into the fall of the following year.

The results of this research were published online in Mammal Study on December 20th.

Paper title: Variation in Fat Accumulation is Associated with Food Availability in Asian Black Bears

Authors: Seigo Sawada, Kahoko Tochigi, Hiroki Kanamori, Sam MJG Steyaert, Shinsuke Koike

URL: https://doi.org/10.3106/ms2025-0018

Background

For wild animals, changes in nutritional status are important factors that are directly related to the survival, growth, and reproductive success of individuals. Therefore, understanding the nutritional status of wild animals is essential for understanding not only the individual wild animals in their natural state, but also the health of the population (Note 1) and changes in the habitat environment.

The amount of fat in the body is one of the most reliable indicators for assessing the nutritional status of wild animals. Animals store energy from food as fat, and use stored fat as an energy source when performing various activities. In addition to subcutaneous fat (Note 2) and visceral fat (Note 3), which are called body fat, there is bone marrow fat (Note 4) inside the bones. When the animal goes into a state of starvation and its nutritional status decreases, these fats are used in turn. Therefore, measuring the amount of fat in each of them allows for a more accurate assessment of nutritional status. In addition, by measuring the amount of fat in each season, it is possible to verify at what time of year the animal is in a state of satiety or starvation.

Asian black bears (hereinafter referred to as bears) lead a plant-based diet, changing their food types according to the flushing and fruiting of plants in each season. Among them, they eat a large amount of hard mast (e.g., acorns) in the fall and then go into hibernation. Previous study have shown that bears consume 70% to 80% of the energy they consume during the fall months (press release "Autumn Acorns Support Bears' Year ~Black Bear Containment Strategies from the Perspective of Energy Balance~"). But where and how much fat does the bear store the energy it consumes in large quantities? And how and when to use those fats? It was not clear.

Furthermore, since acorns have natural phenomena such as good masting and poor masting (Note 5), the amount of fat stored in bears may also fluctuate from year to year, but how much fat accumulation decreases due to poor masting? How long will the impact resonate? It is also not clear. In this study, we aimed to clarify the effects of seasonal changes in fat accumulation in multiple places in the bear body and the masting of acorns in autumn on fat accumulation.

Research Structure

This research was conducted by Seigo Sawada, Director of the Shimane Prefecture Center for Mountainous Areas, Professor Shinsuke Koike of the Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology Graduate School of Institute of Agriculture Division of Environment Conservation, and Sam Steyaert Associate Professor of the Nord University of Norway (concurrent Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology Graduate School Institute of Global Innovation Research Associate Professor), It was conducted by an international joint research team led by Kahoko Tochigi, a postdoctoral researcher at the National Institute for Environmental Studies. This research was partially supported by the JSPS Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (23K26942), the Ministry of the Environment, the Environmental Restoration and Conservation Agency (4-2502), and the Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology Graduate School Institute of Global Innovation Research.

Research results

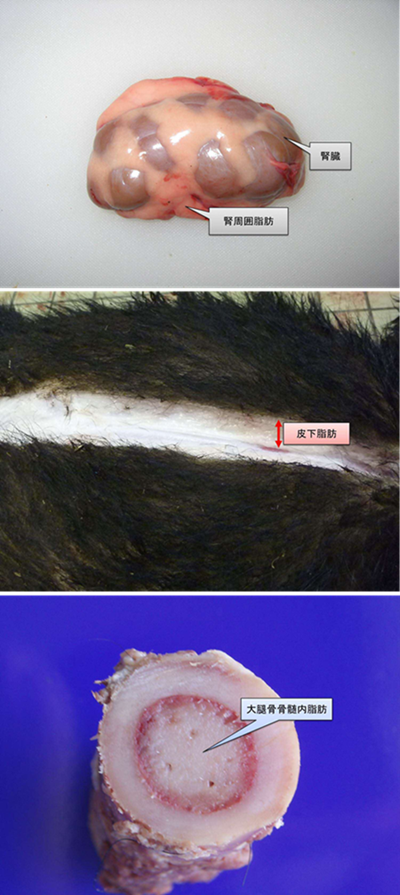

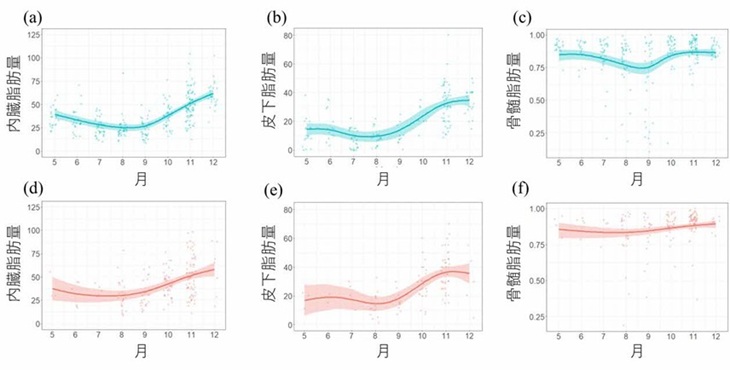

In this study, three types of fat accumulation (subcutaneous fat mass (Note 6), kidney fat accumulation as an indicator of visceral fat (corrected perirenal fat index (Note 7)), and femoral intramedullary fat accumulation as an indicator of bone marrow fat mass) (Figure 1) were measured for 651 bears captured and culled in Shimane Prefecture between 2003 and 2018. These fat masses decreased from spring to late summer (August to September), reached their lowest point in summer, and then increased in autumn (October to December) (Figure 2). Comparing the autumn before hibernation with the spring after hibernation, subcutaneous fat decreased by 62% and visceral fat by 39%. This indicates that hibernating bears used these two types of fat as an energy source.

Furthermore, visceral fat, subcutaneous fat, and bone marrow fat in summer had decreased to 72%, 87%, and 88% of their spring levels, respectively, indicating that bears used these three fats as an energy source from spring to summer. It has been known that bears' energy balance (energy intake minus energy expenditure) is negative during the summer, but the fact that fat accumulation continues to decrease from spring to summer proves that the spring to summer season is a nutritionally challenging time for bears.

These results also allow us to estimate the order in which bears use body fat. Specifically, while visceral and subcutaneous fat are used simultaneously during hibernation, the loss of subcutaneous fat is more pronounced, suggesting that bears may use subcutaneous fat first as an energy source. Furthermore, the loss of over 70% of subcutaneous fat from spring to summer compared to autumn suggests that bears primarily use visceral fat. In particular, it is thought that males began using bone marrow fat after using up most of their visceral fat by early summer. This may be due to the fact that males have larger home ranges than females, which requires more energy. Furthermore, spring and summer are mating seasons (Note 9), and males spend a lot of time competing with other males for females and searching for them, which may prevent them from finding enough time to feed (see press release, "The Unknown Love Affairs of Bears: First Successful Filming of Asian Black Bear Mating Behavior"). It is thought that bears prioritize using subcutaneous fat, which is easy to use during hibernation and fasting, and conserve visceral fat and bone marrow fat as important energy sources for the harsh seasons of spring and summer when food is scarce.

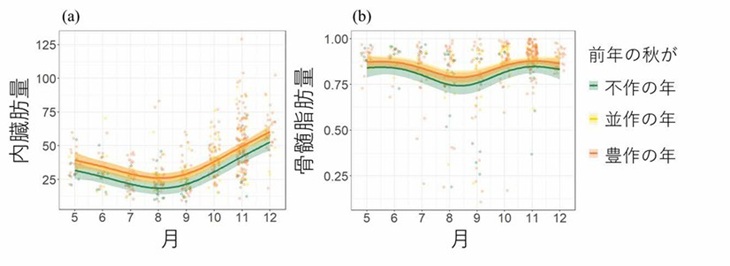

Furthermore, when the relationship between the level of acorn masting on oak trees in the previous year, measured by body fat, and the amount of fat the following year was examined, it was found that when the acorn masting was poor the previous year, the bears had less visceral and bone marrow fat the following year than in years when the previous year's masting was average or bumper. Furthermore, this effect continued into the fall of the following year, indicating that the bears were not fully recovered from their nutritional status after hibernation as they entered summer and autumn. Furthermore, in years when the acorn masting was poor, it is possible that the bears were unable to accumulate sufficient subcutaneous fat during the fall, and that they supplemented their energy needs during the subsequent hibernation by using a lot of visceral fat.

Future developments

From the perspective of body fat accumulation, this study demonstrates the importance of autumn diet and the associated accumulation of fat in various parts of the body for bears to survive the year. Furthermore, these results also have important implications for bear management and damage prevention.

Since the 2000s, there have been incidents of bears intruding in large numbers in autumn in areas where humans are active. This phenomenon has become a serious issue of conflict between humans and bears in Japanese society. The direct trigger for these mass intruding is the poor masting of hard mast, which are the bears' staple food in autumn, and the resulting changes in their behavior. It is also known that the presence of attractants within human settlements encourages bears to appear in areas where humans are active.

Our results show that the year before a poor masting was a good or mediate masting. All of the bears that appeared in settlements and other areas in poor masting years and were captured for nuisance purposes, and most of them had sufficient fat reserves, and were in good nutritional condition. In other words, these results indicate that the factor that causes bears to appear in settlements in poor masting years is not a deterioration in physiological nutritional status due to a decrease in fat reserves in the body, in other words, hunger, but rather the presence of attractive attractants in front of them, such as unharvested persimmons and chestnuts left in the settlements.

This suggests that, regardless of the natural phenomenon of masting, continuing to take measures to prevent bears from entering settlements, such as gradually removing bear-attracting objects and blocking their entry routes, is essential to reducing conflict between humans and bears. These measures, combined with other measures such as zoning management (a method of creating buffer zones between bear habitats and human settlements), are fundamental solutions to reconstruct the tension between humans and bears.

Glossary

Note 1) A certain type of population that lives in a certain area.

Note 2) Fat located just below the skin.

Note 3) Fat that accumulates in the abdominal cavity, around various internal organs.

Note 4) The bone marrow of bones such as the femur is mainly composed of fatty tissue.

Note 5) The amount of fruit (seed) produced by many trees varies greatly from year to year, and in the case of Fagaceae trees, there is a strong tendency for annual fluctuations in production to be synchronized among individuals over a wide range.

The place or space where an individual usually operates.

Note 6) The thickness of the subcutaneous fat at the pubic symphysis is used as an index.

Note 7) The weight of the fat surrounding the kidney is used as an indicator relative to the weight of the kidney itself.

Note 8) Bone marrow is collected from the central third of the femur and dried at 80°C for 24 hours, and the weight ratio before and after drying is used as an index.

Note 9) This refers to the season in which animals engage in reproductive behavior. In the case of bears, this generally refers to the early summer period when they mate.

Figure 1: From top to bottom, examples of visceral fat (corrected perirenal fat index), subcutaneous fat, and bone marrow fat (intramedullary fat in the femur) of an Asian black bear used for measurements.

Figure 2: Seasonal changes in visceral fat (corrected perirenal fat index) (a, d), subcutaneous fat (b, e), and bone marrow fat (intramedullary femoral fat) (c, f) in Asian black bears. Blue indicates data for males (a-c) and red indicates data for females (d-f). Bone marrow fat measurements range from 0% to 100% but were transformed for analysis. In all graphs, the solid line represents the mean predicted by the model, and the shaded area indicates the 95% confidence interval. Actual observed values are indicated by dots.

Figure 3: Seasonal changes in visceral fat (corrected perirenal fat index) (a) and bone marrow fat (femoral intramedullary fat) (b) of Asian black bears, relative to the degree of oak fruiting in the year prior to sample collection. Lines indicate years in which oak masting were good (red), maditate (yellow), or poor (green) in the year prior to sample collection. Bone marrow fat measurements range from 0% to 100% and were transformed for analysis. In all graphs, the solid line represents the mean value predicted by the model, and the shaded areas indicate the 95% confidence interval. Actual observed values are indicated by dots.

◆Inquiries about research◆

Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology Graduate Institute of Agriculture Division of Environment Conservation

Professor Shinsuke Koike

E-mail: koikes (put @ here)cc.tuat.ac.jp

Chief of the Wildlife Control Section, Shimane Prefectural Mountainous Region Research Center

Seigo Sawada

TEL: 0854-76-3819

◆ Inquiries about the press ◆

Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology General Affairs Office Public Relations Office

Tel:042-367-5930

E-mail: koho2 (please put @ here)cc.tuat.ac.jp

Shimane Prefectural Mountainous Area Research Center, Wildlife Control Division

TEL: 0854-76-3819

E-mail: chusankan-choju (insert @ here) pref.shimane.lg.jp

Related Links (opens in a new window)

- Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology Professor Shinsuke Koike Researcher Profile

- Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology Professor Shinsuke Koike Laboratory Website

- Professor Shinsuke Koike, Department of Ecoregion Science Faculty of Agriculture Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology Agriculture and Technology